Table Of Content

- ⚡ Executive Summary

- The Historical Context: From License Raj to Startup India

- Pre-2000: The Constrained Era

- 2000-2014: The Metro-Centric Boom

- 2015-2025: The Great Geographic Shift

- Defining the Bharat Startup Ecosystem Today

- What Qualifies as a “Bharat Startup”?

- By the Numbers: The 2025 Landscape

- The Tier-2/Tier-3 Advantage

- Funding Realities: The Capital Desert and How Founders Navigate It

- The Harsh Truth About VC Access

- The Bootstrapping Imperative

- Alternative Capital Pathways

- When (and How) Bharat Startups Raise External Capital

- Policy & Infrastructure: The Enablers and Gaps

- Government Support Ecosystem

- Digital Infrastructure Revolution

- The Infrastructure Deficit

- Market Opportunities: Where Bharat Startups Win

- Vernacular and Hyperlocal

- Agritech and Rural Economy

- Edtech Beyond English

- D2C and Local Manufacturing

- B2B and Enablement Layers

- The Founder Journey: Real Stories from the Grassroots

- Profile 1: The Bootstrapped Builder—Ramesh Kumar, Jaipur

- Profile 2: The Reverse Migrant—Priya Deshmukh, Nagpur

- Profile 3: The Rural Innovator—Suresh Patel, Anand District, Gujarat

- Founder POV: Classystreet and Mentoring Insights

- Challenges Unique to Bharat Startups

- The Talent Paradox

- Market Education Costs

- The Scaling Dilemma

- Cultural and Social Barriers

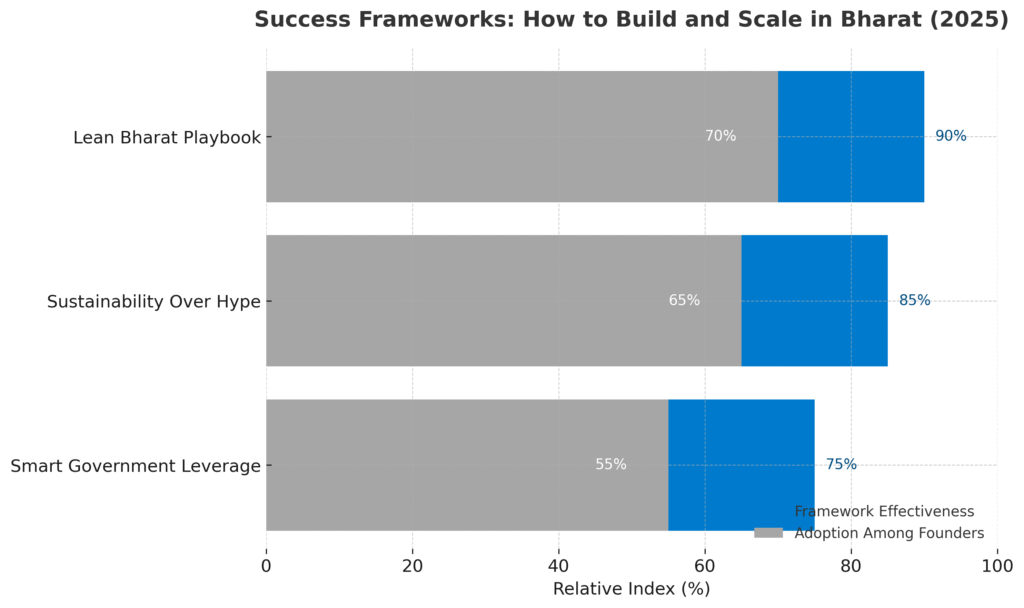

- Success Frameworks: How to Build and Scale in Bharat

- The Lean Bharat Playbook

- Building for Sustainability Over Hype

- Leveraging Government Programs Smartly

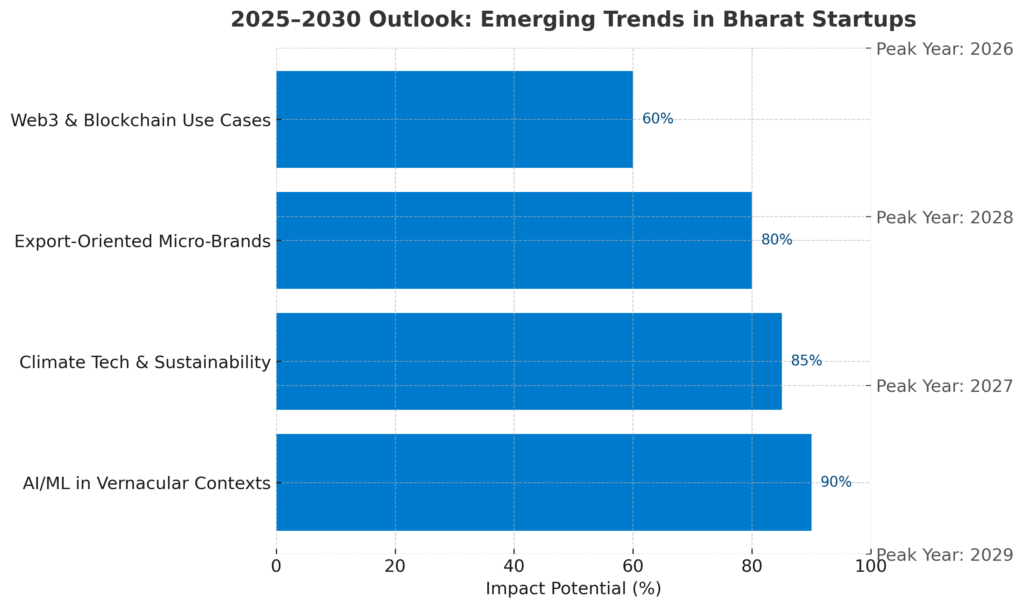

- The 2025-2030 Outlook: What’s Next for Bharat Startups

- Emerging Trends

- Policy Predictions

- The Bharat Unicorn Question

- FAQs

- What is a Bharat startup?

- How much does it cost to start a business in a Tier-2 city?

- Can I get VC funding from a Tier-3 city?

- What are the best sectors for Bharat entrepreneurship?

- How does Startup India help grassroots founders?

- What’s the failure rate of Bharat startups vs. metro startups?

- What are the tax benefits for Bharat startups?

- 📋 Founder’s Action Plan

- Conclusion: Building the Future from Bharat

- Explore Our Comprehensive Guides

- Join the Conversation

- Sources & Government Data

The real India isn’t building in Bengaluru’s glittering co-working spaces or Mumbai’s venture-backed accelerators. It’s launching in Indore’s small manufacturing units, Coimbatore’s textile workshops, and Patna’s mobile repair shops. This is Bharat—and it’s rewriting the rules of entrepreneurship.

⚡ Executive Summary

The “Bharat Startup” wave of 2025 is distinct from the metro startup ecosystem. It prioritizes unit economics over valuation and focuses on solving fundamental infrastructure gaps in agriculture, healthcare, and logistics.

- The Shift: Investors have moved away from “Growth at all costs” to “Profitability first” models found in Tier 2 cities.

- Distribution is King: Successful Bharat startups are building hybrid (Phygital) distribution networks, not just digital ads.

- Policy Tailwinds: New government schemes (DPIIT) are specifically incentivizing startups that manufacture or serve non-metro regions.

While mainstream startup media obsesses over unicorn valuations and funding announcements, a quieter revolution is unfolding across India’s Tier-2, Tier-3 cities, and rural hinterlands. As of March 2025, over 117,000 startups are recognized by the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT), with nearly 58% originating outside the traditional metros of Delhi-NCR, Mumbai, and Bengaluru.

This isn’t just geographic diversification. It’s a fundamental shift in how entrepreneurship happens in India: bootstrapped instead of VC-backed, solving local problems instead of copying Silicon Valley models, building for sustainability instead of growth-at-all-costs. These are Bharat startups—and they represent India’s most authentic entrepreneurial movement since independence.

I’ve spent the last Eleven years building Classystreet from the ground up, mentoring over 500 founders across smaller cities, and observing ecosystem dynamics through engagements with NITI Aayog. What I’ve witnessed is this: Bharat entrepreneurs aren’t trying to become the next Flipkart. They’re creating something entirely different—more resilient, more rooted, and ultimately, more representative of India’s economic reality.

This guide is that untold story. Welcome to Bharat.

The Historical Context: From License Raj to Startup India

Pre-2000: The Constrained Era

For most of India’s post-independence history, entrepreneurship was a privilege, not a right. The License Raj—a labyrinth of permits, quotas, and bureaucratic approvals—made starting a business an ordeal reserved for the well-connected. Between 1947 and 1991, the average Indian entrepreneur needed 57 permits and licenses to operate, with wait times stretching into years.

Small-town India was even more constrained. Without access to capital, connections, or information, aspiring entrepreneurs in places like Rajkot or Bhubaneswar had virtually no path to scale. The economy was effectively closed to grassroots innovation.

The 1991 liberalization changed the regulatory landscape, but not the geographic concentration of opportunity. Capital, talent, and infrastructure remained stubbornly clustered in major metros.

2000-2014: The Metro-Centric Boom

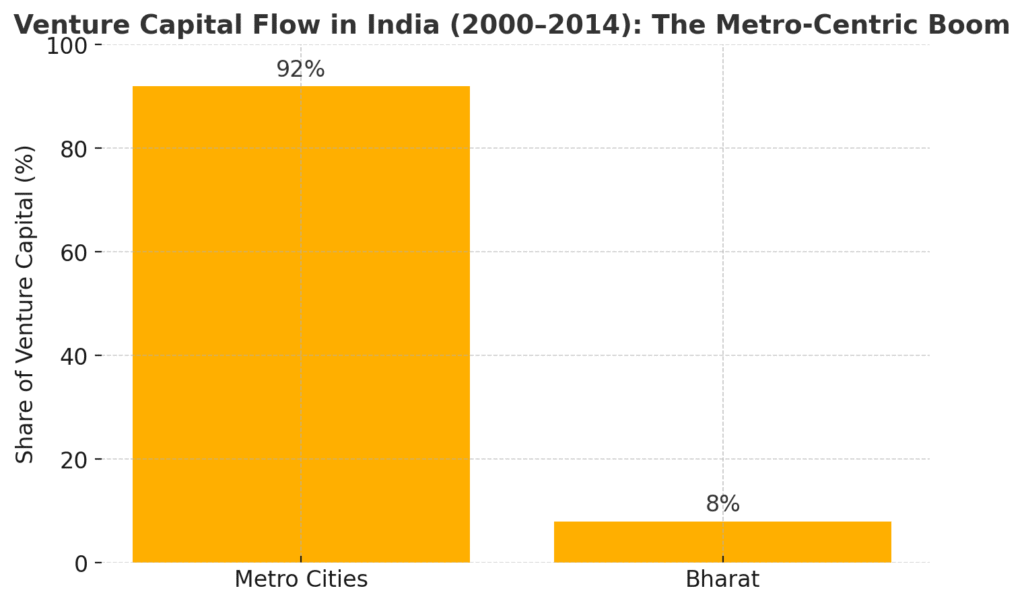

India’s first startup wave was entirely metro-centric. The IT services boom created Bengaluru, Hyderabad, and Pune as tech hubs. The e-commerce revolution of the late 2000s—Flipkart (2007), Ola (2010), Snapdeal (2010)—was funded by global VCs betting on India’s English-speaking, urban middle class.

During this period, over 92% of venture capital flowed into just five cities. The narrative was simple: India’s entrepreneurial story was happening in Tier-1 cities, period. Bharat was a market to be served, not a place to build from.

Why was Bharat left behind? Three reasons: infrastructure deficits (unreliable internet, poor logistics), talent drain (anyone ambitious left for metros), and investor bias (VCs couldn’t do diligence in places they’d never visited). The entrepreneur from Kanpur or Nashik had no seat at the table.

2015-2025: The Great Geographic Shift

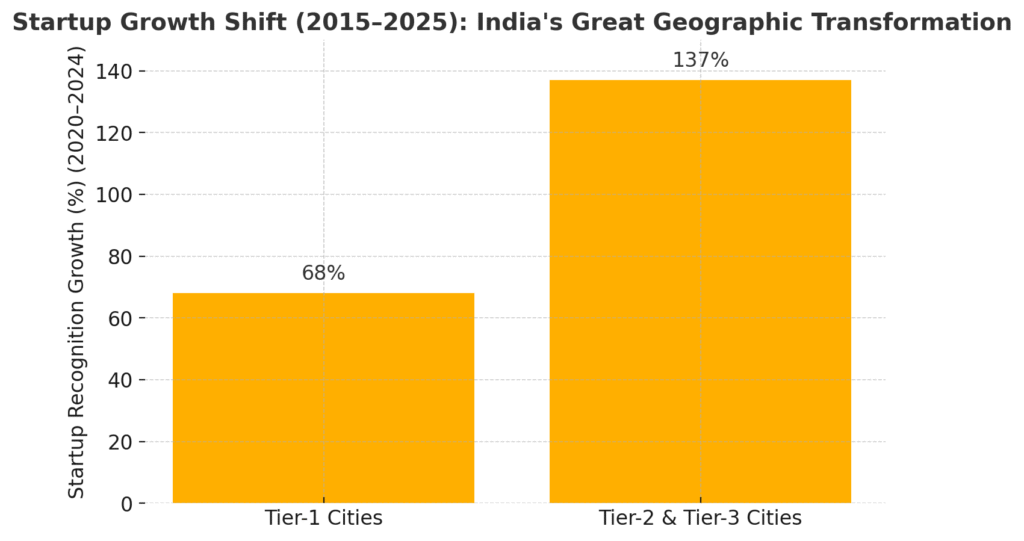

Everything changed in the last decade. The Startup India initiative, launched in January 2016, recognized startups beyond traditional definitions and offered tax benefits and compliance relief. By 2025, the initiative has facilitated recognition for startups across 670+ districts—bringing entrepreneurship to India’s remotest corners.

But policy wasn’t the only catalyst. Digital India’s infrastructure push transformed the ground reality. Between 2016 and 2023, Reliance Jio’s aggressive rollout made mobile internet accessible in nearly every tehsil. Data costs plummeted from ₹300 per GB to under ₹10. Suddenly, a chai shop owner in Aurangabad could research suppliers, accept digital payments, and scale operations using just a smartphone.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated this shift. Reverse migration brought thousands of professionals back to their hometowns—armed with metro experience, global exposure, and startup know-how. DPIIT data shows that between April 2020 and December 2024, startup recognition in Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities grew by 137%, compared to just 68% in Tier-1 cities.

Today’s Bharat startup isn’t an anomaly. It’s the new normal.

Defining the Bharat Startup Ecosystem Today

What Qualifies as a “Bharat Startup”?

Not every business outside Mumbai qualifies as a Bharat startup. The distinction isn’t just geographic—it’s philosophical and operational.

Geographic Definition: Bharat startups originate in Tier-2 cities (populations between 50,000-1 million), Tier-3 towns (under 50,000), or rural clusters. Think Kota, Raipur, Madurai, Vijayawada—places outside the traditional startup maps.

Philosophical Definition: These ventures solve problems rooted in local contexts. They’re not importing Western business models; they’re building from ground-up insights. A logistics startup in Kanpur isn’t competing with Delhivery—it’s solving last-mile delivery in cities where national players don’t reach.

Economic Definition: Bharat startups typically bootstrap or raise minimal external capital. Their revenue models are tied to vernacular markets, regional languages, and lower average revenue per user (ARPU). Profitability isn’t a future milestone—it’s a survival requirement.

By the Numbers: The 2025 Landscape

As of March 2025, India’s startup landscape looks radically different than a decade ago:

- Total DPIIT-recognized startups: 117,254 (up from 452 in 2016)

- Startups from non-metros: 67,865 (58% of total)

- Districts with recognized startups: 673 out of 766

- Female-founded startups in Tier-2/3: 48% (higher than the 39% metro average, per DPIIT’s Women Entrepreneurship Platform data)

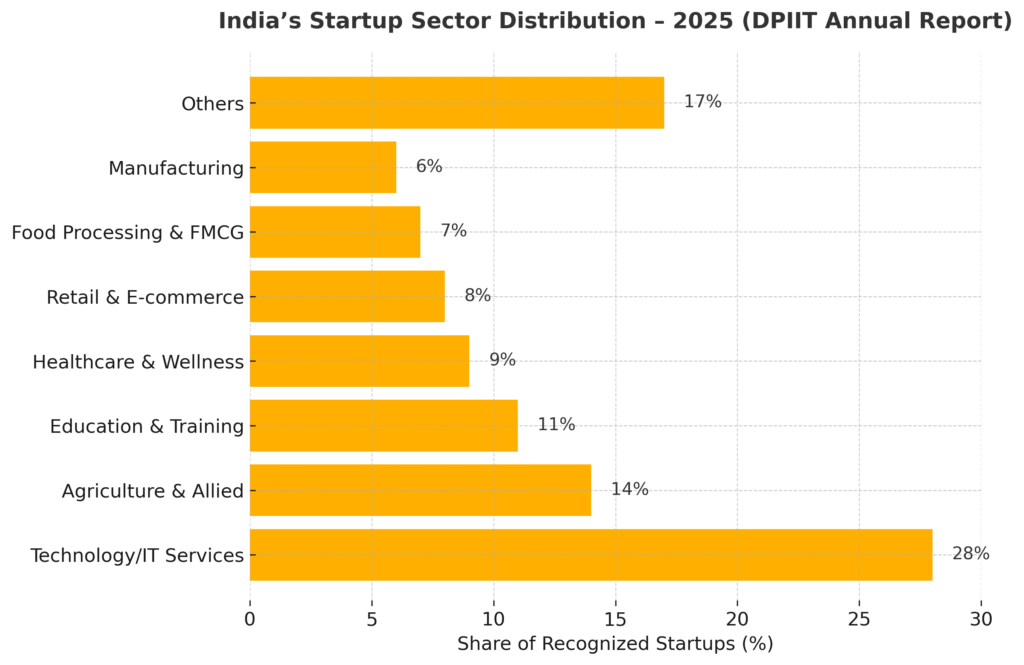

Sector Distribution (DPIIT Annual Report 2024-25):

- Technology/IT services: 28%

- Agriculture & allied sectors: 14%

- Education & training: 11%

- Healthcare & wellness: 9%

- Retail & e-commerce: 8%

- Food processing & FMCG: 7%

- Manufacturing: 6%

- Others: 17%

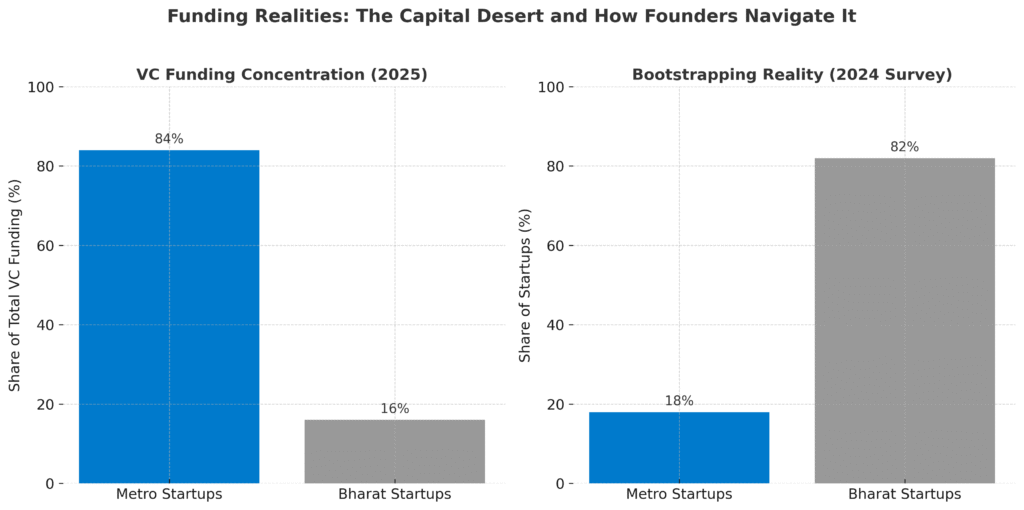

Funding Reality: Despite representing 58% of startups, Bharat ventures captured only 11% of total venture funding in 2024 (₹8,200 crore out of ₹75,000 crore, according to Bain-IVCA India Venture Capital Report 2025). The funding-per-startup ratio tells the story: metros average ₹18 crore per funded startup; non-metros average ₹2.3 crore.

Employment Generation: According to the MSME Ministry’s 2024 Annual Report, startups in Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities collectively employed 2.8 million people as of December 2024—with significantly lower attrition rates (18% annually vs. 32% in metros).

The Tier-2/Tier-3 Advantage

Why would anyone choose to build in Bhosari over Bengaluru? Because the economics are fundamentally different.

Lower Operational Costs: Office space in Indore costs ₹15-25 per sq.ft. versus ₹80-120 in Bengaluru’s Koramangala. Engineering talent costs 40-60% less. Customer acquisition costs are 30-50% lower. The burn rate that kills metro startups in 18 months can sustain a Bharat venture for 4-5 years.

Proximity to Problem Statements: When you’re building a fintech product for kirana stores, living in a city with 10,000 such stores—where you shop, where your family shops—gives you unbeatable insight. You’re not doing market research; you’re living it.

Talent Availability and Retention: Yes, metros have more IIT grads. But Bharat has thousands of qualified engineering and commerce graduates who prefer stable opportunities close to home. Attrition rates below 20% are common—a luxury metro startups can’t imagine.

For deeper insights into regional dynamics, ecosystem infrastructure, and how Tier-2/3 cities are competing, explore our comprehensive analysis: [The Startup Ecosystem in Bharat (2025)].

Funding Realities: The Capital Desert and How Founders Navigate It

The Harsh Truth About VC Access

Let’s be blunt: if you’re building in Jaipur or Visakhapatnam, venture capital is functionally inaccessible.

The 2025 Bain-IVCA report shows that 84% of VC funding went to startups in Delhi-NCR, Bengaluru, and Mumbai. Angel investments show similar concentration: 89% of angel deals happen in metros. The few VCs who claim “geography-agnostic” investing quietly maintain offices only in Bengaluru and Gurgaon.

Why? VCs operate on portfolio economics. They need pattern recognition, quick due diligence, and easy follow-on access. A partner can meet five Bengaluru startups in a day; reaching Bhopal takes a day itself. The economics don’t work for early-stage cheques below ₹5 crore.

For Bharat founders, this isn’t a complaint—it’s operating reality. You build accordingly.

The Bootstrapping Imperative

Over 82% of Bharat startups are entirely self-funded, according to a 2024 survey by the Indian Angel Network’s Bharat Fund. This isn’t a choice—it’s necessity creating capability.

Bootstrap culture in Bharat means extreme capital efficiency. Every rupee matters. You don’t hire before you have revenue. You don’t scale before you’ve proven unit economics. You build for cash flow, not hockey-stick growth.

When I started Classystreet in 2015, I had ₹75,000 in savings and zero connections to investors. That constraint forced clarity: what can we build with almost nothing? We landed our first client in 43 days, became profitable in month six, and didn’t think about external funding for three years. That discipline—born from necessity—still defines how we operate today.

For founders facing similar constraints, there’s a proven playbook. Master the art of capital-efficient launches with our tactical guide: [The ₹50,000 Startup: How to Launch with Minimal Capital].

Creative Funding Sources that Bharat founders actually use:

- Family pooling: The most common first cheque, typically ₹2-8 lakhs from parents, uncles, or extended family

- Community crowdfunding: Informal networks in towns where everyone knows everyone; a successful jeweler funding a nephew’s tech venture

- Microfinance institutions: MUDRA loans (up to ₹10 lakhs) remain the lifeline for micro-enterprises, though approval rates vary wildly by state

- Pre-selling/advance payments: Convincing early customers to pay upfront, effectively funding operations through receivables

- Side hustles: 67% of Bharat founders maintain consulting or freelance income in their first 18 months

Alternative Capital Pathways

Government schemes dominate the early-stage funding landscape for Bharat startups:

MUDRA (Micro Units Development and Refinance Agency): Offers loans up to ₹10 lakhs without collateral. As of March 2024, MUDRA had disbursed ₹35 lakh crore since 2015—though average loan size is just ₹40,000, and tech startups often don’t qualify under manufacturing/services criteria.

SIDBI (Small Industries Development Bank of India): Runs multiple schemes including the Fund of Funds for Startups (₹10,000 crore corpus). However, only 147 startups from Tier-2/3 cities received funding through SIDBI in FY 2023-24, totaling just ₹680 crore.

State Government Funds: Progressive states like Karnataka, Kerala, Telangana, and Gujarat run their own startup funds. Kerala’s KSUM has funded 180+ startups with ₹15-50 lakhs each; UP’s Startup Policy 2020 allocated ₹1,000 crore but disbursed only ₹140 crore by 2024.

Revenue-Based Financing (RBF): The emerging alternative to equity. Companies like Velocity, GetVantage, and Klub offer capital (₹20 lakhs-₹2 crore) in exchange for a percentage of monthly revenue until a cap is reached. No equity dilution, no board seats—ideal for bootstrapped, revenue-generating Bharat startups.

Bank Lending: Theoretically available, practically difficult. Banks demand collateral that early-stage startups don’t have. The CGTMSE (Credit Guarantee Fund Trust for Micro and Small Enterprises) should solve this, but documentation requirements and risk-averse bank managers mean rejection rates above 70%.

When (and How) Bharat Startups Raise External Capital

Some Bharat startups do eventually raise VC/angel funding—but typically after demonstrating far more traction than metro counterparts. The playbook:

Demonstrate proof of concept completely bootstrapped: VCs want to see that you can execute without their money first. Reach ₹50 lakhs-₹1 crore in annual revenue, prove unit economics, show repeatability.

Build relationships early, raise later: Start attending startup events, join accelerators (even virtually), connect with angels who mentor. When you’re ready to raise in year 2-3, you’re not a cold email.

Target regional angels and sector-specific VCs: Don’t waste time pitching Sequoia. Focus on angels from your region (they understand the context) and sector-focused funds (agritech funds for agritech startups, not generalist VCs).

Prepare for asymmetric diligence: Metro startups face 4-6 weeks of diligence. Bharat startups face 3-6 months, often with in-person visits, customer reference checks, and heightened scrutiny. Be ready.

Avoid predatory terms: Some investors exploit geographic information asymmetry. Watch for: liquidation preferences above 1x, founder vesting longer than 4 years, drag-along rights without founder protections, aggressive valuation caps on convertible notes.

Policy & Infrastructure: The Enablers and Gaps

Government Support Ecosystem

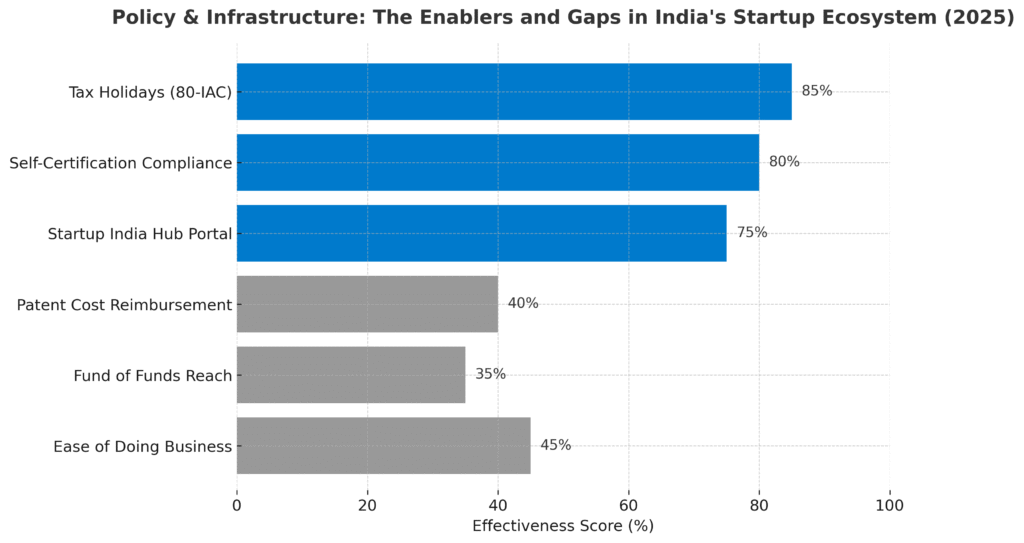

The Startup India initiative launched in 2016 with three pillars: simplification and handholding, funding support and incentives, and industry-academia partnership. Nearly a decade in, what’s actually working?

What’s Useful:

- Tax holidays (Section 80-IAC): Three years of tax exemption for DPIIT-recognized startups is real money saved, especially in years 2-4 when you’re first profitable

- Self-certification compliance: Nine labor and environment laws can be self-certified, reducing inspector harassment significantly

- Startup India Hub portal: Centralized registration, grievance redressal, and learning resources—genuinely helpful for first-time founders

What’s Still Broken:

- Patent cost reimbursement: Promises 80% rebate on filing fees, but reimbursement process takes 18-24 months with 50% rejection rates

- Fund of Funds: ₹10,000 crore corpus, but capital reaches founders only through SIDBI-approved VCs who prefer metro deals anyway

- Ease of doing business: Despite reforms, closing a business still takes 4.3 years on average; insolvency resolution remains painful

State-Level Policies: The variance is enormous. Kerala’s KSUM offers ₹15 lakh grants with minimal strings; Telangana’s T-Hub provides world-class infra; Gujarat’s iCreate has incubated 250+ startups. Meanwhile, some states have “policies” that exist only on paper.

From my NITI Aayog engagement experiences, I’ve observed that the central government’s intent is genuine, but execution depends entirely on state and district administrations. Where local officials are entrepreneurial themselves (often IAS officers with private sector stints), ecosystems thrive. Elsewhere, schemes gather dust.

Digital Infrastructure Revolution

If there’s one factor that made Bharat entrepreneurship possible at scale, it’s digital infrastructure—specifically, cheap data and digital payments.

The Jio Effect: When Reliance Jio launched in September 2016 with free data and ₹50/month plans, it didn’t just disrupt telecom—it democratized entrepreneurship. By 2024, India had 882 million internet users (TRAI data), with 58% in Tier-2/3/rural areas. Data costs dropped 99%, from ₹300 per GB (2015) to under ₹10 (2025).

What does this mean practically? A garment manufacturer in Tirupur can now:

- Research international fashion trends on YouTube

- Source raw materials via WhatsApp supplier networks

- List products on Meesho/Flipkart with smartphone photos

- Track shipments in real-time

- Communicate with customers in Tamil via vernacular e-commerce

All from a ₹12,000 smartphone with ₹200/month internet. That’s the revolution.

UPI and Digital Payments: The Unified Payments Interface processed 131 billion transactions in 2024, totaling ₹200 lakh crore. UPI penetration in Tier-2+ cities reached 76%, enabling micro-businesses to go cashless without expensive POS machines. The QR code revolution—powered by BharatQR and UPI—has turned every street vendor into a digital merchant.

The Infrastructure Deficit

Despite progress, significant gaps remain:

Logistics and Supply Chain: E-commerce logistics reach Tier-2 cities efficiently, but last-mile connectivity to Tier-3/rural areas remains expensive and unreliable. A startup shipping products from Jalgaon to rural Maharashtra faces 3-5 day delays and 40% higher costs than Bengaluru-Mumbai routes.

Talent Gap: While engineering colleges have mushroomed across smaller cities (1,200+ engineering colleges exist outside metros), quality varies wildly. Finding experienced product managers, growth marketers, or senior technical leads in Tier-2/3 cities remains difficult. Remote work has helped, but cultural and time-zone challenges persist.

Co-Working and Incubation Infrastructure: Tier-1 cities have hundreds of co-working spaces; Tier-2 cities might have 2-3, often poorly managed. Incubators exist in name (attached to engineering colleges) but lack meaningful mentorship, network access, or funding connections.

Internet Reliability: Mobile internet coverage is wide but shallow. 4G speeds average 12 Mbps in smaller cities vs. 30 Mbps in metros. Power backup and fiber broadband remain unreliable outside city centers. For tech startups running cloud infrastructure or video services, this is a daily operational challenge.

Market Opportunities: Where Bharat Startups Win

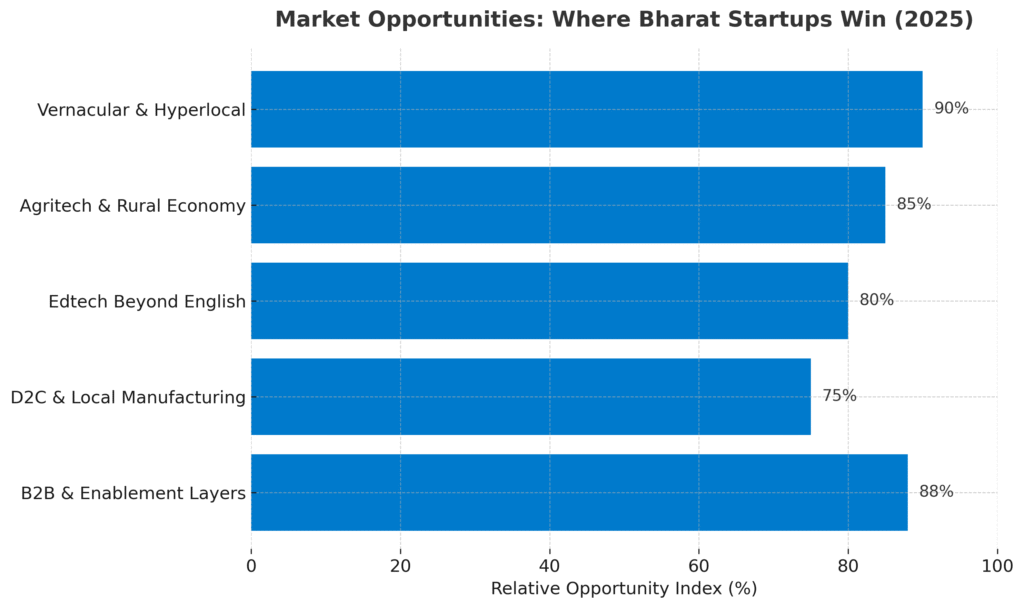

Vernacular and Hyperlocal

India has 22 official languages and over 121 spoken languages. Yet, until recently, nearly all digital services were English-first. The vernacular revolution is creating massive opportunities.

Language-First Products: ShareChat (15+ Indian languages, 180 million users), Moj (short-video platform, 160 million users), and DailyHunt (350 million users) proved that vernacular-first can scale. But the real opportunity isn’t competing with these giants—it’s building vertical-specific vernacular tools:

- Legal and compliance services in Marathi, Bengali, Tamil

- Healthcare advice platforms in Telugu and Malayalam

- Financial literacy content in Hindi and Gujarati

- Vocational training videos in Punjabi and Kannada

Hyperlocal Services: National players struggle with unit economics in smaller cities. This creates white space for regional champions in:

- Grocery and fresh produce delivery (Tier-2 cities need 45-minute delivery too)

- Home services (plumbing, electrical, cleaning)—but with trusted local networks

- Healthcare at home (sample collection, physiotherapy, elder care)

- Tutoring and test prep in regional languages

The key insight: These aren’t “small” businesses. Dominating grocery delivery in 10 Tier-2 cities can generate ₹100+ crore revenue with better margins than fighting for Bengaluru marketshare.

Agritech and Rural Economy

Agriculture contributes 18% of India’s GDP and employs 42% of the workforce—yet receives less than 2% of startup funding. For Bharat founders close to farm ecosystems, this is the opportunity gap of the decade.

Farm-to-Market Platforms: Eliminating middlemen who extract 30-40% margins. DeHaat (₹1,700 crore revenue, serves 2 million farmers) and Ninjacart (₹3,000 crore revenue) have proven the model, but hundreds of crops and regions remain unserved.

Input Supply Chains: Seeds, fertilizers, pesticides reach farmers through opaque, commission-heavy channels. Digital platforms offering transparent pricing, quality assurance, and doorstep delivery are winning farmers’ trust.

Financial Inclusion: Only 28% of farmers access formal credit; 72% rely on moneylenders charging 24-48% annual interest. Fintech platforms offering crop loans, insurance, and savings products have massive TAM—but require deep rural relationship networks that metro founders can’t build.

Case Study—AgroStar: Founded in 2013 and headquartered in Pune, AgroStar delivers agri-inputs directly to farmers via its app (available in 10+ languages). It serves 5 million farmers, processes 50,000+ orders daily, and reached profitability in 2022. The founder, Shardul Sheth, came from a farming family—his understanding of farmer psychology and credit cycles was the unfair advantage.

Edtech Beyond English

India’s edtech boom focused on urban, English-medium students. But 85% of Indian students study in vernacular medium schools. The real market is regional language education.

Skill Development and Vocational Training: India needs to skill 400 million people by 2030 (National Skills Development Corporation target). Most will be trained in Hindi, Tamil, Bengali—not English. Platforms offering trade-specific training (electrician, beautician, CNC operator) in vernacular languages can tap government NSDC subsidies while building sustainable businesses.

Vernacular Content Platforms: YouTube proved vernacular education works (countless Hindi, Tamil, Telugu channels teach everything). But there’s room for structured, curriculum-aligned, exam-focused platforms in regional languages with better monetization than YouTube ads.

Exam Prep in Regional Languages: Civil services, banking, SSC, state government exams—millions prepare in Hindi and regional languages. Apps like Adda247, Testbook, and Oliveboard have scaled, but localized competition with better vernacular UX can capture state-specific exam markets.

D2C and Local Manufacturing

Bharat’s manufacturing heritage—textiles in Tirupur, leather in Kanpur, brassware in Moradabad, handicrafts across villages—is now finding direct consumer markets.

Handicrafts, Textiles, Food Products: Platforms like Meesho, Amazon Karigar, and Flipkart Samarth have enabled thousands of artisans to sell nationally. But the real upside is building own brands: a Madhubani painting artist becoming a lifestyle brand, a Banarasi weaver launching premium home décor, an organic spice farmer creating a D2C FMCG brand.

How Bharat Brands Compete on Authenticity: Metro consumers increasingly value “story” over specs. A handloom sari from Pochampally with the weaver’s video story commands premium pricing over factory-made alternatives. Bharat entrepreneurs have inherent authenticity—they just need to package and market it.

Export Potential: The Government e-Marketplace (GeM) and Amazon Global Selling have made exports accessible. A wooden toy maker in Channapatna can now ship to US and Europe directly. In 2023-24, over 12,000 MSMEs used GeM for government procurement, with 18% from Tier-3 cities.

B2B and Enablement Layers

While consumer businesses grab headlines, the biggest Bharat opportunity might be B2B infrastructure.

SaaS for Small Businesses: India has 63 million MSMEs; most run on pen-paper or basic Excel. SaaS solving their workflows—inventory management, billing, vendor payments, compliance—is a ₹50,000 crore opportunity. Khatabook (digital ledger, 20 million businesses) and Dukaan (e-commerce for retailers) have proven demand.

Supply Chain Tech: Logistics, warehousing, and distribution networks in Bharat are inefficient but enormous. Tech enabling better route optimization, real-time tracking, or vendor coordination can extract value from billion-dollar traditional industries.

Fintech for MSMEs: Invoice discounting, working capital loans, digital accounting, GST filing—the financial infrastructure layer for small businesses is still nascent. Startups like OfBusiness (fintech + B2B commerce, valued at $5B) show the scale possible.

The Founder Journey: Real Stories from the Grassroots

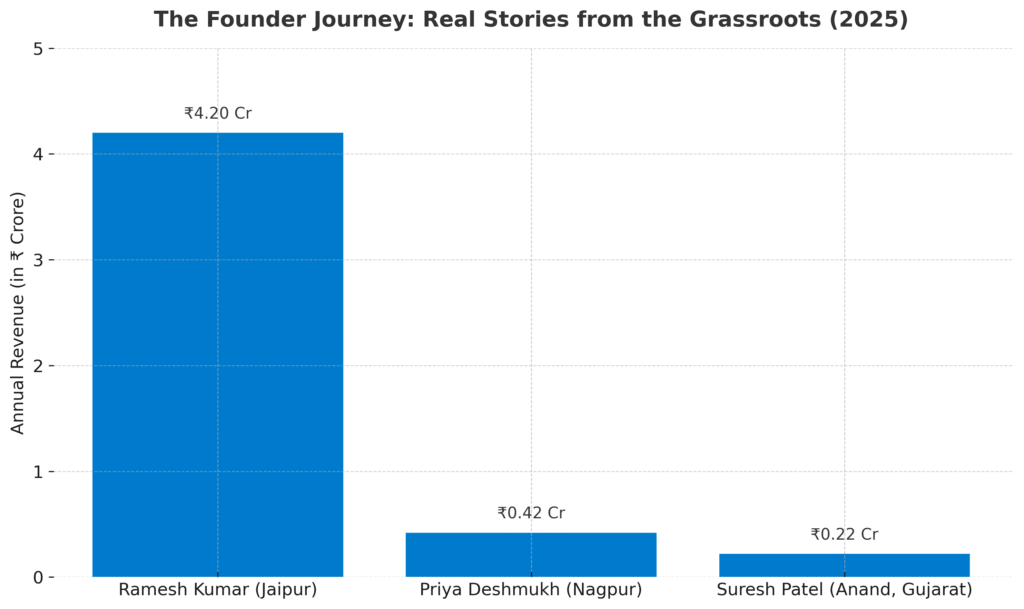

Profile 1: The Bootstrapped Builder—Ramesh Kumar, Jaipur

Ramesh Kumar quit his ₹8 lakh/year corporate job in Gurgaon in 2019 to return to Jaipur. His problem statement was personal: his father’s textile printing business was losing ground to cheaper Chinese imports. Rather than watch the family business die, Ramesh decided to digitize it.

With ₹2.5 lakhs in savings, he built a basic website, learned Google Ads through YouTube, and listed the business on IndiaMART. First order came in 47 days—₹35,000 from a Surat-based garment manufacturer. By month six, online orders exceeded walk-in business.

Challenges were constant: hiring designers who understood both traditional block printing and digital design, convincing artisan workers that digital orders were “real,” managing cash flow when bulk orders required 50% material advance but customers paid on 30-day credit.

Three years in, the business does ₹4.2 crore annually, employs 28 people, and has never raised external funding. Ramesh’s lesson: “In Tier-1 cities, you raise money to hire talent to build products. In Tier-2, you build products to generate revenue to hire talent. The sequence is inverted—and that makes all the difference.”

This philosophy—building for sustainability before growth—is explored deeply in our framework: [Innovation vs. Sustainability: Trade-offs Every Founder Must Navigate].

Profile 2: The Reverse Migrant—Priya Deshmukh, Nagpur

Priya spent seven years in Bengaluru as a product manager at a B2B SaaS startup. When COVID hit in March 2020, she returned to Nagpur to be with family. What was meant to be a 3-month break turned permanent.

Living in Nagpur, she noticed a gap: the city had 200+ small coaching institutes (for JEE, NEET, CA) but zero software to manage them. They used WhatsApp for attendance, Excel for fees, and lost thousands to administrative inefficiency.

In November 2020, Priya launched CoachOS—a simple web app for coaching center management. She charged ₹2,000/month, onboarded her first customer (her own coaching teacher from school days), and iterated based on feedback. By September 2022, 140 coaching centers across Maharashtra and MP were using CoachOS, generating ₹42 lakhs annual recurring revenue.

Her unfair advantage: she understood product-market fit from her Bengaluru experience but had authentic access to coaching owners in Tier-2 cities who trusted her because she “spoke their language”—literally and figuratively.

Priya never raised funding. “VCs would ask about TAM and tell me to expand to all India in year one. That would have killed us. We grew city by city, built referrals, achieved 92% retention. Slow felt risky then; now I realize it was the only way to build something real.”

Profile 3: The Rural Innovator—Suresh Patel, Anand District, Gujarat

Suresh Patel never went to college. He managed his family’s 15-acre dairy farm in a village near Anand, supplying milk to the local cooperative. In 2018, he noticed a problem: veterinary doctors visited villages only twice a week, but cattle health issues didn’t wait.

With guidance from an agricultural extension officer and ₹35,000 in savings, Suresh launched “GauSwasth”—a WhatsApp-based telemedicine service for cattle. Farmers could send photos/videos of sick animals; qualified vets (Suresh partnered with five retired vets) would diagnose and prescribe within hours. He charged ₹100/consultation—low enough for small farmers, high enough to sustain the business.

Within 18 months, GauSwasth was serving 1,200 farmers across 40 villages. Revenue: ₹22 lakhs annually. Suresh hired two full-time coordinators and three part-time vets. He also started selling veterinary medicines at transparent prices, adding a second revenue stream.

The challenges were unique: farmers didn’t trust “phone doctors” initially, smartphone adoption was low among older farmers, payment collection required physical cash pickup initially (digital came later), and vet availability during peak farming seasons was difficult.

But Suresh had one thing metro founders can’t replicate: trust. Everyone knew his family, his farm, his reputation. When he said GauSwasth worked, people believed him.

His story exemplifies the deep insights we’ve gathered studying rural innovators. For more on these patterns, explore: [Grassroots Entrepreneurship: Lessons from Rural India].

Founder POV: Classystreet and Mentoring Insights

I started Classystreet in 2015 with ₹75,000, zero clients, and a simple thesis: small businesses need professional marketing but can’t afford metro agency rates. We’d offer the same quality at 60% of the price—and actually answer client calls.

The first six months were brutal. I coded our website myself (badly), cold-called 200+ prospects (3 responded), and worked from a ₹3,000/month desk in a shared office. Our first client paid ₹22,000 for 3 sarees. I remember the exact amount because it validated that someone would pay for our work.

Eight years later, we’ve worked with 4800+ clients across 400+ cities, built a team of 12, and achieved profitability every year except the first. We’ve never raised external funding—not because we’re anti-VC, but because we never needed to. Our clients paid our salaries. Revenue funded growth.

Through mentoring 500+ Bharat founders (via NITI Aayog connections, local startup events, and informal networks), I’ve identified common patterns:

What Success Looks Like:

- First revenue within 90 days (not 18 months of “building in stealth”)

- Founder-led sales until ₹50 lakhs ARR (you can’t outsource understanding your customer)

- Obsessive focus on unit economics from day one (every deal must make sense)

- Building in public within their local community (trust compounds faster than marketing)

- Comfortable saying “no” to opportunities that don’t fit their core strength

Common Failure Patterns:

- Copying metro business models without adapting to local context

- Hiring too fast before revenue justifies it (the “we’ll grow into the team” trap)

- Chasing VC funding instead of customers (spending 6 months pitching instead of selling)

- Over-investing in tech/product before validating demand (the “build it and they’ll come” fallacy)

- Underestimating the mental game—isolation, family pressure, skepticism from peers

The Mental Game: This is the part nobody talks about. Building in a Tier-2/3 city means your IIT batchmates are at Google earning ₹40 lakhs; your neighbors think you’re unemployed; your family asks when you’ll get a “real job.” The ecosystem support that metro founders take for granted—co-founders to vent with, mentors who’ve been there, peer networks—barely exists.

The founders who make it develop deep internal conviction. They stop caring about external validation. They measure success by customer impact, not LinkedIn posts. It’s lonely, but it’s also liberating.

Challenges Unique to Bharat Startups

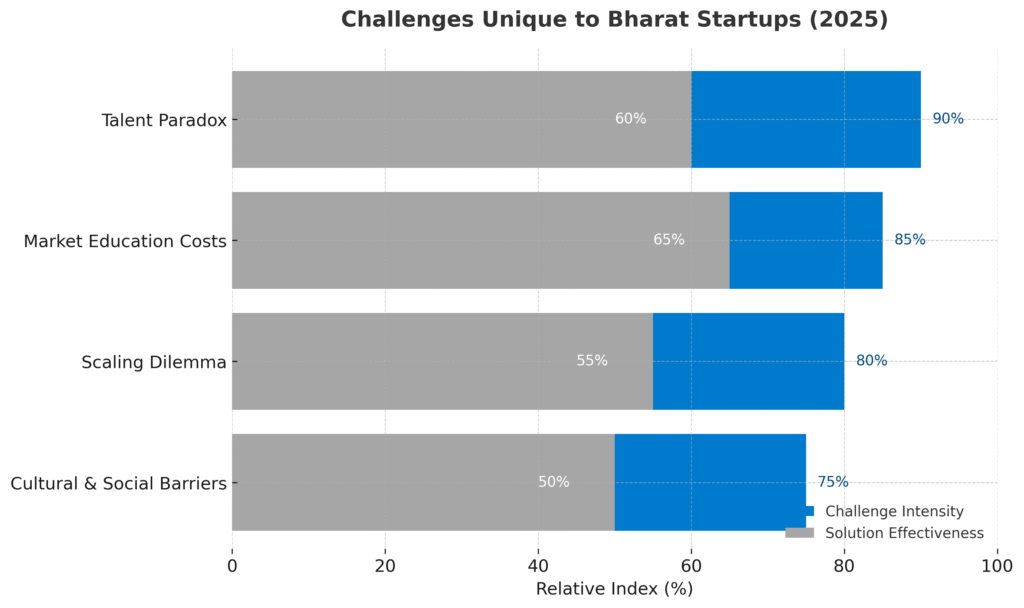

The Talent Paradox

Bharat cities produce hundreds of thousands of engineering, MBA, and commerce graduates annually. Yet hiring remains the #1 challenge founders cite.

The issue isn’t quantity—it’s aspiration. The ambitious graduates want to work at TCS, Infosys, or migrate to Bengaluru/Pune. The ones who stay often lack the hustle, ownership mindset, or skill depth that startups need.

Quality vs. Cost Trade-offs: You can hire a fresh graduate at ₹3-4 lakhs in Indore versus ₹8-12 lakhs in Bengaluru. But that Bengaluru hire might have interned at a funded startup, knows modern tools, and requires less handholding. The Indore hire needs 6-12 months of training before they’re productive.

Many Bharat founders spend enormous time on training—essentially running internal bootcamps. It works, but it’s a tax metro founders don’t pay.

Senior Talent Scarcity: Finding experienced product managers, growth marketers, or tech leads outside metros is nearly impossible. They exist but are already employed at the few successful local companies or work remotely for metro startups.

Remote Work—Opportunity and Limitation: Post-COVID, remote work helped. Bharat founders can now hire from anywhere. But cultural friction is real: metro talent often doesn’t understand local market nuances, time zone challenges emerge with global clients, and attrition remains high when remote employees get metro offers.

The founders who crack this: hire for attitude over skill, invest heavily in training, create ownership through ESOPs/profit-sharing early, and build strong culture despite distributed teams.

Market Education Costs

In metro markets, customers understand SaaS subscriptions, free trials, and digital payments. In Bharat markets, every transaction requires education.

Customer Acquisition in Low-Digital-Literacy Markets: Convincing a 55-year-old shop owner to adopt your billing software isn’t about product features—it’s about trust-building, hand-holding through setup, and proving value over weeks. Your sales cycle isn’t 2 calls; it’s 8 touchpoints over 3 months.

Building Trust Without Brand Legacy: In Tier-2/3 cities, people buy from people they know. A new brand without local references struggles. This is why Bharat startups often grow through community networks, local influencer partnerships, and word-of-mouth rather than digital ads.

Long Sales Cycles: B2B sales in smaller cities can take 4-6 months from first contact to closed deal. Decision-makers need to consult family, verify references locally, and often want to “see other customers first.” This creates a chicken-and-egg problem: you need customers to get customers.

The workaround: free pilots, money-back guarantees, and relentless customer service that generates referrals.

The Scaling Dilemma

Every Bharat founder eventually faces this question: When do we expand beyond our home market?

The Trap of Premature Scaling: You’ve achieved product-market fit in Bhopal. You have 200 customers, ₹80 lakhs annual revenue, and 40% margins. VCs (if you’ve managed to attract one) or advisors push you to “expand to 10 cities” to reach “scale.”

But scaling destroys unit economics. Your Bhopal success came from founder-led sales, local trust, and deep customer relationships. Replicating that in Indore requires hiring salespeople, marketing spend, and operational complexity. Revenue grows, but profits crater.

Managing Unit Economics in Low-ARPU Environments: If your average customer pays ₹2,000/month (vs. ₹20,000 for metro SaaS), your cost of acquisition must be proportionally lower. But it’s often not—sales effort is similar. This is why many Bharat startups struggle with VC growth expectations: the path to ₹100 crore revenue requires 50,000 customers, not 5,000.

The framework that helps founders navigate this is understanding when to prioritize innovation versus sustainability—when to grow versus consolidate. We explore this critical trade-off: [Innovation vs. Sustainability: Trade-offs Every Founder Must Navigate].

The Right Scaling Strategy: Successful Bharat startups scale slowly, sequentially, and profitably:

- Dominate one city completely before entering the second

- Expand to adjacent cities where you have existing network/trust

- Hire regionally (not centrally) with local leaders who understand context

- Keep founder-customer connection even at scale through community building

- Prioritize retention over acquisition (90%+ retention can drive growth at 40% annual rate)

Cultural and Social Barriers

The entrepreneurial journey in Bharat carries social weight that metro founders rarely face.

Family Pressure and the “Stable Job” Mindset: In smaller cities, family isn’t just nuclear—it’s extended. Your career choices impact family reputation. Quitting a bank job to start a business isn’t celebrated; it’s questioned. The “what will relatives say?” factor is real and psychologically taxing.

Many founders maintain side income or part-time employment for 1-2 years just to satisfy family concerns. It’s not ideal, but it’s pragmatic.

Gender Disparities: While DPIIT data shows 48% female entrepreneurship in Tier-2/3 cities, ground reality is complex. Women face additional barriers: mobility restrictions, family responsibilities, skepticism from vendors/customers, and limited access to male-dominated business networks.

The women who succeed often do so by building women-centric businesses (beauty, wellness, education) where they have authentic insight, or by partnering with supportive family members who handle external-facing roles initially.

Caste and Community Dynamics: This is the uncomfortable truth rarely discussed: In many smaller cities, business relationships still follow community lines. Access to credit, supplier networks, and customer trust can be mediated by caste/community affiliations.

Forward-thinking founders break these barriers through transparency, digital platforms that bypass traditional gatekeepers, and explicit merit-based practices. But acknowledging the challenge is the first step.

Success Frameworks: How to Build and Scale in Bharat

The Lean Bharat Playbook

Building in Bharat requires a distinct playbook—one that embraces constraints as advantages.

Start Micro, Validate Relentlessly: Don’t build for 18 months and launch. Build the minimum for 18 days and test. Your first product can be a WhatsApp group, a Google Form, or a manually fulfilled service. The goal is customer feedback, not perfect tech.

Community as Co-Creator: In metro startup culture, you “discover” customers. In Bharat, you involve them from day one. Your early customers become advisors, referrers, and co-owners of your success. This isn’t just good karma—it’s survival strategy.

Frugal Innovation Principles:

- Can this feature be manual before we automate? (Save 6 months of development)

- Can we rent/share instead of buying? (Office space, equipment, even talent)

- Can customers self-serve with training instead of needing support staff?

- What’s the absolute minimum to deliver value?

For practical, tactical guidance on capital-efficient launches, explore: [The ₹50,000 Startup: How to Launch with Minimal Capital].

Building for Sustainability Over Hype

The metro startup playbook is growth-at-all-costs, blitzscaling, and “get big fast.” The Bharat playbook is different—because it has to be.

Profitability-First Mindset: Target profitability by month 12-18, not year 5. This forces discipline: pricing that covers costs plus margin, conservative hiring, and sustainable customer acquisition. It also means you survive when funding winters hit.

When to Say No to Dilutive Funding: Not all capital is good capital. If an investor wants 30% equity for ₹50 lakhs but demands 10x growth in 3 years, the math might not work. That capital comes with expectations that could kill your business.

Better question: Do we need this capital? Many Bharat founders raise funding because it feels like validation, not because they need it. If you’re cash-flow positive and growing 30-40% annually, patience beats dilution.

The Long Game Approach: Building in Bharat is a 10-year game, not a 3-year exit plan. You’re building an institution, not a flip. That changes everything: hiring for cultural fit, building brand trust slowly, reinvesting profits rather than extracting, and creating employment in your community.

This isn’t romanticization—it’s strategy. The founders I’ve seen succeed measure success by resilience, not headlines.

Leveraging Government Programs Smartly

Government schemes are abundant—but navigating them requires skill.

Which Schemes Actually Deliver:

- MUDRA loans (Shishu category, up to ₹50,000): Fastest approval, minimal documentation, useful for inventory/equipment

- Startup India recognition: Free, provides tax benefits and easier compliance

- State startup grants (where available): Better than central schemes because decision-makers are local

- GeM registration: If you have products/services governments buy, this is free revenue

Which Schemes Are Time Sinks:

- Most incubator programs attached to engineering colleges (lack real mentorship/network)

- Patent reimbursement (process is so slow and complex, just pay for patents yourself)

- Central government tenders (unless you have prior government sales experience, stay away)

How to Navigate Bureaucracy: The secret isn’t paperwork—it’s relationships. One conversation with the right district official can fast-track approvals that online forms can’t. Attend local startup events where officials speak, volunteer for government committees, and build rapport before you need favors.

From my NITI Aayog observations: The system wants to help, but it’s designed for scale, not speed. Patient founders who learn the system do benefit; those expecting Silicon Valley efficiency get frustrated and quit.

The 2025-2030 Outlook: What’s Next for Bharat Startups

Emerging Trends

AI/ML Adoption in Vernacular Contexts: The next wave of AI won’t be ChatGPT in English—it’ll be voice-based assistants in Hindi, Tamil, and Bengali helping farmers with crop advice, shop owners with inventory management, and students with homework. Bharat founders who understand local language nuances and context will build the AI layer for non-English India.

Climate Tech and Sustainability Focus: As climate impact hits agriculture and water availability, climate-resilient solutions will emerge from the ground up. Expect startups in drought-resistant farming, water recycling, sustainable packaging, and renewable energy—built by founders who live with these challenges daily.

Export-Oriented Micro-Brands: Global consumers want authentic, story-driven products. A Kashmiri saffron farmer or a Banarasi weaver can now build global D2C brands via Shopify and Instagram. The next decade will see hundreds of “Made in Bharat, Sold to World” micro-brands doing ₹10-50 crore revenue each.

Web3 and Crypto—Realistic Assessment: Despite hype, Web3 adoption in Bharat will lag metros by 3-5 years. Regulatory uncertainty, low crypto literacy, and limited use cases beyond speculation mean most Bharat founders should focus elsewhere. That said, blockchain for supply chain transparency (especially in agriculture and handicrafts) has real potential.

Policy Predictions

Expected Reforms:

- Startup exit simplification: Current insolvency timelines (4+ years) will compress to 12-18 months, removing the fear of entrepreneurial failure

- GST simplification for MSMEs: Quarterly filing instead of monthly, with simplified compliance for businesses under ₹5 crore revenue

- State-level competition: More states will launch aggressive startup policies to compete with Karnataka and Telangana—expect Bihar, UP, Odisha to emerge as surprising players

State Competition for Startup Ecosystems: Just as states compete for manufacturing investment, they’ll compete for startups. Expect: subsidized office space, fast-tracked clearances, dedicated startup cells with decision-making power, and state-sponsored accelerators with actual funding (not just mentorship).

IPR and Patent Reforms: Faster patent processing (target: 12 months vs. current 24-36 months) and stronger enforcement will help deep-tech and hardware startups from Bharat compete globally.

The Bharat Unicorn Question

Will we see a unicorn ($1B+ valuation) emerge from a Tier-2/3 city?

The Case For:

- Several startups are already on trajectory: Innovaccer (Noida), Udaan (Bengaluru but serves Tier-2/3 retailers), FirstCry (Pune)

- Market size is enormous—Tier-2+ cities represent 65% of India’s consumer spending

- Cost advantages and capital efficiency mean Bharat startups can reach profitability faster

The Case Against:

- VC preference for metro founders remains strong (network effects, talent access)

- Most Bharat startups don’t have unicorn ambitions—they’re building sustainable businesses

- TAM constraints: A startup dominating Rajasthan might do ₹500 crore revenue but struggle to expand nationally

Realistic Assessment: We’ll likely see several “mini-corns” (₹1,000-5,000 crore valuations) from Bharat by 2030—highly profitable, regionally dominant, sector-leading companies that never get unicorn press but employ thousands and generate hundreds of crores in revenue. That might be more valuable than unicorn status anyway.

Most Likely Sectors: Agritech (farm-to-market platforms), hyperlocal services (regional champions in logistics/delivery), vernacular edtech, and B2B SaaS for MSMEs.

Timeline: 2027-2029 will be the window. Companies founded in 2020-2022 (post-COVID reverse migration wave) will have 5-7 years of execution, proven models, and scaled revenue. If macro conditions support and capital is available, we’ll see breakout stories.

FAQs

What is a Bharat startup?

A Bharat startup is an entrepreneurial venture originating from India’s Tier-2, Tier-3 cities, or rural areas, typically characterized by bootstrapped or minimal external funding, solving problems rooted in local contexts, and building for vernacular or regional markets. Unlike metro startups that often import Western models, Bharat startups are built from ground-up insights into non-urban India’s needs, constraints, and opportunities.

How much does it cost to start a business in a Tier-2 city?

Starting costs vary by sector, but a service-based business can launch with ₹25,000-75,000 (covering basic website, initial marketing, licenses, and 3 months of operational expenses). Product-based businesses need ₹1-5 lakhs (inventory, logistics setup, compliance). Tech startups can start with ₹50,000-2 lakhs (development tools, hosting, initial hires if needed).

The key advantage: operational costs in Tier-2 cities are 40-60% lower than metros—office space, talent, and customer acquisition all cost less. For step-by-step guidance on launching with minimal capital, see: [The ₹50,000 Startup: How to Launch with Minimal Capital].

Can I get VC funding from a Tier-3 city?

Honestly? It’s very difficult. Less than 5% of VC funding goes to startups outside India’s top 5 cities. VCs prefer metros for portfolio efficiency—easier diligence, quick follow-ons, and pattern recognition.

However, you can raise funding if you: demonstrate strong traction (₹50 lakhs+ ARR with proven unit economics), target sector-specific or regional VCs who understand your market, build relationships over 12-18 months before pitching, and be prepared for longer diligence timelines.

Better strategy: bootstrap to profitability first, then raise for scale (if needed). Many successful Bharat founders never raise VC and don’t regret it.

What are the best sectors for Bharat entrepreneurship?

Based on DPIIT data, founder success rates, and market opportunities:

Agritech: Farm-to-market, input supply, agri-fintech

Hyperlocal services: Grocery, home services, healthcare at home

Vernacular edtech: Skill development, exam prep in regional languages

D2C manufacturing: Handicrafts, textiles, food products with authentic stories

B2B SaaS for MSMEs: Billing, inventory, compliance software

Fintech for underserved markets: Lending, payments, savings for small businesses

Choose sectors where you have authentic insight—either from personal experience or deep local networks.

How does Startup India help grassroots founders?

Startup India provides:

Tax holidays: 3 years of income tax exemption under Section 80-IAC (saves lakhs in taxes)

Self-certification compliance: 9 labor and environmental laws can be self-certified, reducing inspector harassment

Access to government tenders: Recognized startups can bid without prior experience/turnover requirements

Networking and learning: Hub portal connects founders with mentors, investors, and peer networks

Limitation: Most funding programs under Startup India flow through VCs who prefer metro deals, so direct financial benefit is limited for Bharat founders. The real value is compliance relief and legitimacy.

What’s the failure rate of Bharat startups vs. metro startups?

No official data exists, but ecosystem observations suggest:

Metro startups: ~60-70% fail within 3 years (high burn rate, VC pressure, intense competition)

Bharat startups: ~40-50% fail within 3 years (bootstrapped means lower burn, but market education costs and talent constraints increase risk)

Bharat startups that survive past year 3 have higher long-term survival rates because they’re profitable and resilient—not dependent on next funding round.

How do I access government schemes like MUDRA or SIDBI?

MUDRA Loans:

Visit nearest public/private bank or NBFC

Submit application with business plan (simple 2-3 page document)

Provide KYC documents, address proof, and business registration

For Shishu category (up to ₹50,000), approval typically takes 7-15 days

No collateral required, but guarantor might be needed

SIDBI Support:

Visit sidbi.in and explore relevant scheme (Fund of Funds, direct lending, etc.)

Most SIDBI funding flows through partner VCs/NBFCs, not directly to startups

For direct schemes, apply through district MSME offices

Pro tip: Visit your local District Industries Centre (DIC)—they can guide you through multiple schemes and fast-track approvals.

What are the tax benefits for Bharat startups?

If you’re DPIIT-recognized and meet eligibility criteria:

Section 80-IAC: 100% tax exemption for 3 consecutive years out of first 10 years (you choose which 3)

Section 56 exemption: Angel investments don’t attract “angel tax”

GST benefits: Simplified monthly returns for startups under ₹5 crore revenue

ESOP tax: Employees can defer tax on ESOPs by 5 years

Important: These benefits apply only to DPIIT-recognized startups incorporated as Private Limited or LLP (not sole proprietorship). Get your startup recognized at startupindia.gov.in—it’s free and takes 2-3 weeks.

📋 Founder’s Action Plan

Conclusion: Building the Future from Bharat

The story of Indian entrepreneurship is being rewritten. For decades, it was a story of English-speaking, IIT-educated founders in Bengaluru and Gurgaon building for India’s top 10%. That story isn’t wrong—it’s just incomplete.

The fuller story includes Ramesh digitizing his father’s textile business in Jaipur, Priya building SaaS for coaching centers in Nagpur, and Suresh creating cattle telemedicine in a Gujarat village. It includes the 67,865 startups recognized by DPIIT from non-metro cities, the 2.8 million jobs they’ve created, and the ₹2.3 lakh crore in value they’re building—quietly, profitably, sustainably.

Bharat entrepreneurship isn’t a category—it’s the new mainstream. It’s India’s economic geography redistributing from three metros to 600+ cities. It’s founders solving local problems with local insights, building for vernacular markets, and creating wealth in their communities instead of migrating to create wealth elsewhere.

This shift matters because it’s inclusive. When entrepreneurship happens in Patna, Kozhikode, and Jamshedpur—not just Bengaluru—it distributes opportunity, retains talent, and keeps wealth circulating locally. It makes Indian capitalism more democratic.

At Webverbal, our mission is to decode this movement—to tell these stories, share these frameworks, and build a knowledge commons for Bharat founders. Because the founders in Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities don’t need someone to inspire them with Silicon Valley myths. They need tactical guidance on MUDRA loans, unit economics, and navigating local bureaucracy. They need peer networks, honest mentorship, and recognition that their path is valid even if it doesn’t end in unicorn headlines.

If you’re building in Bharat, know this: Your constraints are creating capabilities that metro founders don’t have. Your capital efficiency, customer intimacy, and resilience are unfair advantages. The game is different—not easier or harder, just different.

Explore Our Comprehensive Guides

- Launch with minimal capital: [The ₹50,000 Startup: How to Launch with Minimal Capital]

- Navigate critical trade-offs: [Innovation vs. Sustainability: Trade-offs Every Founder Must Navigate]

- Learn from rural innovators: [Grassroots Entrepreneurship: Lessons from Rural India]

- Understand the broader ecosystem: [The Startup Ecosystem in Bharat (2025)]

Join the Conversation

Subscribe to our newsletter for weekly insights, founder stories, and tactical guides for building in Bharat. Follow us on LinkedIn where we’re building India’s most authentic founder community. Or book a consultation—we work with founders navigating these exact challenges.

The future of Indian entrepreneurship isn’t happening in co-working spaces with bean bags and cold brew. It’s happening in small offices above mobile shops, in spare rooms converted to “headquarters,” in chai-fueled late nights after family dinners.

It’s happening in Bharat. And it’s just getting started.

Sources & Government Data

- DPIIT (Startup India) — official recognition & census data

- NASSCOM — strategic reports on Indian tech startups

- IVCA / Bain & Co — India Venture Capital funding reports

- Economic Survey of India — chapter on innovation & startups

Note: This guide synthesizes data from the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT) to provide an accurate snapshot of the ecosystem.